The path to making short films, part 4

I consider post-production to be the easiest stage of the filmmaking journey. It's also the final phase of the "writing" of the film. Editing and sound are the parents of the final, beautiful baby.

This month has been something, hasn’t it? The WGA strike is the big thing that everyone in the film industry has been talking about, of course. Personally, I’ve been planning and engaged in the logistics for a move out of Providence to Glens Falls, NY, while also prepping for our Frigid Kickstarter launch (see below).

The move has entailed a fair bit of driving about eight hours there and back several times, and that’s time I can’t write or do anything meaningful other than think or listen to music, which is why my writing output has fallen off a cliff in the past month. Such is life.

I wanted to get into the meat of this post, but first, a quick word from our s̷p̷o̷n̷s̷o̷r̷ Kickstarter project! Here’s our ultra rad video that we produced for our pitch.

We launched yesterday (May 17) and have been blown away by the responses and support we’ve received thus far. We achieved 11% funding in the first day, thanks to everyday people like you, who are excited about the prospect of what this film might turn out to be, which we hope will be a super scary, super stylish, smart story with heart and heart-pounding visuals.

We have an ambitious vision for it, and we’ll need your help to execute on it. If you can support us, please hit the pledge button on our Kickstarter page and check out our rewards tiers. We’ve tried to make each reward as value-packed as possible.

The path endeth here—or does it?

So. You’ve done it! The short film footage is in the can. Now all you have to do is assemble it in the edit, add in sound effects and music, render it out, and voila, your film has been born into the world, a new creation!

The post-production pipeline is a bit more technical in that much of the work is handled on a computer. In many cases, every piece of the post-production process is digital. Unless you’re one of a handful of people on the planet shooting on film, you’ll be working with digital media the rest of this process.

Post production is broken up into its component parts:

Sound design

Editing

Visual effects

Color grading

Final mix and output

Often there is overlap on these pieces, as editing and sound design and visual effects are all tuned and fine-tuned in concert with each other. Color grading can happen in stages, where a visual palette is determined beforehand by the director and cinematographer, and then that look is “graded” by a colorist in post. That may get tweaked and adjusted along the way, or to accommodate visual effects insertions or late editorial changes.

The key to managing this portion of the process is to ensure you have a solid plan and vision for what you want to achieve and a process for accomplishing each piece. I’ll get into each piece below, and I hope you don’t mind but I plan on geeking out a little bit.

Sound

First, let's talk about one of my favorite parts of post-production: sound design. You might think a film’s success lies in its image (and you’re not wrong), but at least in some circles, it’s not the image, but the sound that makes or breaks a film.

Sound design is what brings a scene to life and creates an immersive experience for the viewers. From footsteps to background music, there's a lot of thought that goes into each sound. We work with sound designers to craft the audio for each scene, placing and blending sounds together to create a seamless, engaging experience on the screen.

Depending on the quality of audio captured on set, you may end up replacing some or all of it with sound recorded in a clean environment, such as a recording booth, or a recreated environment to mimic the shooting location. Actor dialogue may need to be re-recorded, in a process called ADR (Automatic Dialogue Replacement). This is where you sync up the picture while the actor re-records their lines in a sound booth or insulated location. Exterior shoots may require this depending on the environment (windy days are particularly prone to requiring ADR). You may also need to clean up dialogue by tweaking individual words (if a dog was barking during every take, it could require some re-recording of individual lines, for instance). My first feature film I produced was an ultra-low budget film called 13 Months of Sunshine. About 90% of the dialogue was re-recorded. We couldn’t afford a recording studio, so we sound insulated a closet and had the actors come in to record their lines. We used the in-camera monitor as playback so they could sync up their lines. While it wasn’t sexy, it did the job!

Beyond the ADR, sound design and sound effects hold the power to add extra layers to the visuals and bring out the emotions while dramatically influencing the mood of the scene. Sound design is the general tonal fabric of the picture, dictated by the story and the themes you’re wanting to convey, while sound effects bring life to each scene and can guide and manipulate perspectives. You may use library sound effects—or effects from a pre-existing collection of sounds, which you layer into the sound track, or you can record all new, original sound. Sometimes, you may need to record “foley”—the so-called sync sound effects you hear whenever anything is shown on screen. Rain might be created by crinkling paper. The sound of a giant boulder rolling down a hill might be recreated by a Honda Civic rolling down a concrete driveway (famously, this is how the sound of the boulder in Raiders of the Lost Ark was created). Clothes swishing or footsteps or the sound of a knife plunging into someone’s gut can all be created on a stage by a foley artist (or you in your living room). However, from a budget perspective, it might be more economical to simply find sound effects in a library.

The last component of sound is music. Music can add meaning to the story. Melodies can signal characters. Dissonance can engender tension or fear. Silences bring depth and prompt suspense. Music is composed, and later added to the final output during the mixing process in post-production. In most cases hiring a composer for an original soundtrack might be cost prohibitive, but you can often use a library of pre-composed music, which, while not necessarily ideal, can be a way to deliver effective music or soundscape while not destroying a budget.

“Film sound is rarely appreciated for itself alone but functions largely as an enhancement of the visuals: by means of some mysterious perceptual alchemy, whatever virtues sound brings to film are largely perceived and appreciated by the audience in visual terms.

The better the sound, the better the image.”

—Walter Murch

Editing

Now, let's move on to one of the most crucial aspects in post-production: editing. Editing a film is an alchemical process, in which sound and image are combined in unique formations, which, when applied into a structure, form a cohesive narrative. Even “bad” films have this!

Film footage comes in a selection of takes; unique perspectives of a scene shot from various angles with different takes. Our goal during editing is to mix and match the takes to see what works and what doesn’t. Much like the editing phase of a paper or essay, individual parts have to work together and appear like a cohesive whole by the end.

I actually started my career in the film industry, not as a writer or producer, but as an editor. The work I did was pretty basic. But what I learned—most of what I picked up on—was from watching other movies, especially movies in which editing was celebrated for being in some way revelatory or innovative.

Walter Murch, one of the most celebrated film editors in the industry, has contributed significantly to the field of film editing, and has probably been the most respected film editing theorist as well as practical, working industry editor. His exceptional understanding of the visual and auditory language of film editing earned him three Oscars over a four-decade career. His work has always pushed the boundaries of cinematic storytelling and sound design. Murch’s innovative approach involved using natural and synthetic sounds to create an immersive soundscape that complemented the visuals and enhanced the emotional impact of the film. His use of layered soundtracks, complex crossfades, and unique audio perspectives set a new standard for sound editing.

Murch’s expertise and mastery of film editing are rooted in his deep understanding of both visual and auditory storytelling. He is known for his ability to manipulate sound and image to create an immersive and engaging narrative that leaves viewers emotionally affected. Murch’s work has revolutionized the way sound is used in film, and his contributions have set a benchmark for future filmmakers.

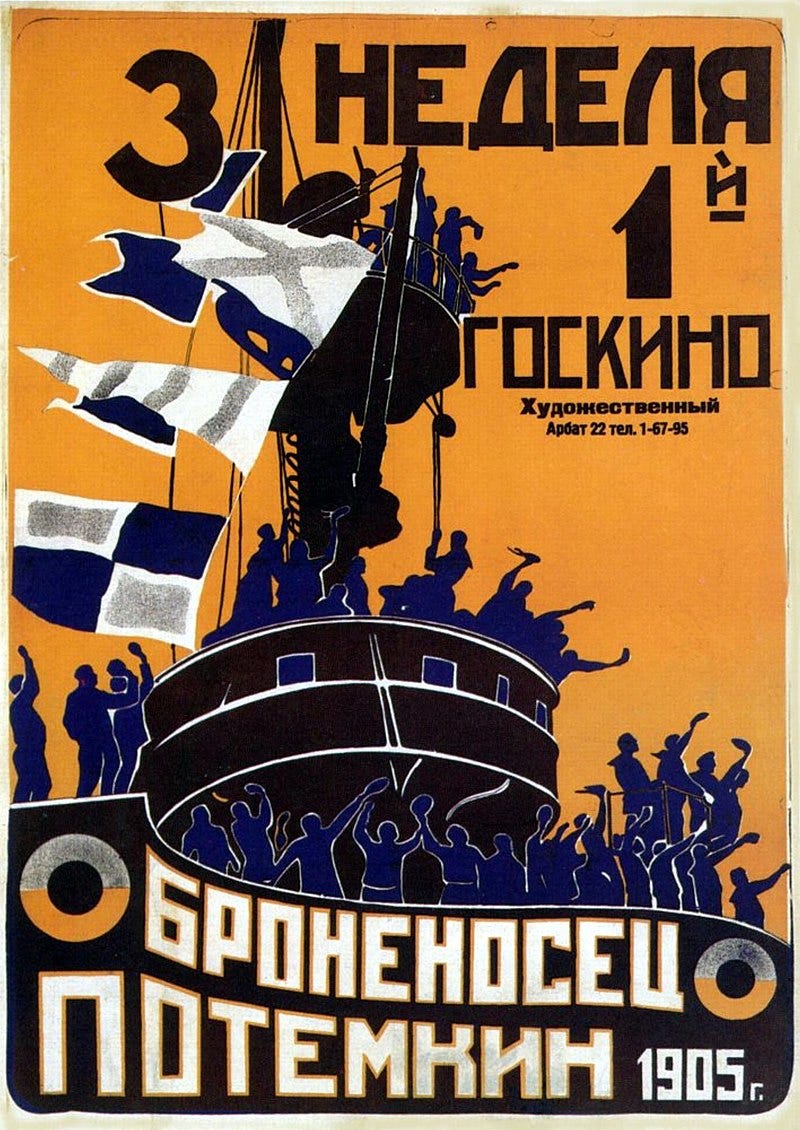

Further back in time, Sergei Eisenstein was a celebrated Russian director who pioneered some of the most essential editing techniques we use today. Probably the most famous example of his work would be the montage. Sergei Eisenstein's theory of montage involved the sequencing of shots in a specific way to create a particular emotional or intellectual response in the audience. Eisenstein believed that the juxtaposition of images was the foundation of cinematic storytelling. Montage was based on the idea of the “collision” of images, where two or more shots are combined to create a new meaning or idea that is not present in the individual shots themselves. For Eisenstein, this collision of images created “intellectual montage,” which appealed to the audience's mind and emotions in a profound and compelling way.

Eisenstein's believed that the unique nature of film storytelling, and editing in particular, had the power to incite social and political change. He believed that the juxtaposition of images could be used to create a dialectical process, where ideas clash and collide in a way that creates a new understanding or synthesis that is greater than the sum of its parts.

To achieve these effects, Eisenstein developed several techniques of montage, including the use of contrasting images, parallel editing, and metric editing. He saw editing as a way to create a rhythm and tempo that would influence the audience’s emotions and thoughts, and he believed that the placement of shots was just as important as the content of the individual shots themselves.

Eisenstein’s ideas about the power of editing and the creation of meaning through montage have shaped the way that film is made and continue to be studied and applied by filmmakers around the world.

Why do I mention these two innovators here? For one, I know practically all I know about film editing from Eisenstein and Murch; they are in some ways under-sung cinematic heroes for me. More to the point, I think any short filmmaker could learn an entire college course by reading Murch’s In the Blink of an Eye or watching (and hearing!) any film Murch worked on. Similarly, one can become an editor, at least academically speaking, by watching and studying Sergei Eisenstein’s films, such as Battleship Potemkin or Alexander Nevsky (probably his most famous works).

From these two artists, we learned image and sound are joined in holy harmony. And yes, while I got a little carried away with this part, I think it’s necessary to sometimes remember that filmmaking is an art first, and that the practical application of the art has source basis in our emotional human response system. We live and breathe movies through the fateful combination of image and sound that brings new meaning into the world. It is this fact that makes the edit the “third rewrite” of the film (the first being the writing, the second being the production). It is in this process that the film becomes its final, beautiful form (and yes, even “bad” films are beautiful).

Color Grading

Have you ever noticed how some films have a certain color palette or mood? That's no accident. Color grading is the process of adjusting and enhancing the colors in each shot to create a cohesive look and feel for the film. This includes adjusting brightness, contrast, saturation, and more. Colorists make sure each shot looks just right and fits the overall vision for the movie. They’ll usually work directly with the director and sometimes the cinematographer to shape the final shot visual “tone.”

A good color grade ties in with the overall story and tone of the film. It's important for the colors to evoke emotion, like a purple hue for sadness or a blue hue for coldness. Contrast can create depth and draw the viewer's eye to particular parts of the frame. Saturation can be used to make colors pop, or to desaturate a scene to create a more muted, subdued effect. Black levels help give the film a cinematic look and feel.

Visual Effects

Next up, we have visual effects. Whether it's adding a CGI creature or compositing different shots together, visual effects can take a scene to the next level (or, you know, make it look horrible). Of course, you don't want the effects to be too noticeable; the effects ideally should look seamless and believable, or even invisible. Effects artists’ work is best when it isn’t noticed.

From pre-production meetings with directors to post-processing in After Effects, the VFX process is both intricate and crucial for creating those "Wow!" moments. Firstly, everyone needs to be on the same page when it comes to the goals of a particular shot or scene, hence the pre-production meetings. Directors and sometimes cinematographers work with VFX artists to create and integrate these effects into the film.

Raw footage is reviewed and often cleaned up with rotoscope software before finalizing the effects with both digital modeling and texturing. For creatures or animated characters, those assets are animated, lit and rendered. It's not unheard of to layer visual effects upon visual effects, so everything needs to then match up perfectly too, hence compositing multiple VFX layers together. Once the components are finished, they go through a process called rendering, where the computer creates multiple frames from the assembled VFX data. Later, these images complement or replace any part of raw footage. When done skillfully, viewers won't know where the reality ends, and the visual effects begin. There may also be color grading involved, depending on the level of complexity of the shot, and when the final render is delivered to the editor.

Subtitling and Captions

To ensure that the tale reaches the global audience without any language barriers, subtitles come in play. They cater to the diverse needs of viewers worldwide. Apart from the basic translation, there are also captions for the hearing-impaired individuals that provide a better understanding of the story by describing all the sound effects and music included. Both subtitles and captions get synced along with the dialogue, and timing is edited to perfection to fit right into the flow so that it adds to engaging viewer experience.

So what’s left?

While your film might be finished, the work has only just begun. You still have to market it, right? This is something I may cover in a future post. For now, I think I’ve more than overwhelmed you. But I hope it’s helpful in seeing the big picture. There’s lots of stuff—details I didn’t get into—that you should feel free to email me about or leave a comment if you’re not sure about something.

I’m here to help.

Now, the rest of this week I’ll be finishing this damn move. I’ll be happy to be writing the next post from my new home in Glens Falls, NY.

Thanks for reading, all. Pax!